Reimagining the Museum.

In this blog we take a look at how a multistate approach to cultural venue technology can benefit visitors and curators alike.

Date

12/1/2022

Sector

Insights

Built Environment

Third Sector

Subject

Technology Research

Article Length

8 minutes

Reimagining the Museum.

Share Via:

Cultural institutions hold the past and tell the story of the present. But how do we establish their form and nature in the future, and to a greater extent, how do we ensure public interest and access to historical artefacts remains engaging?

This week at Arch we’ve been pondering how museums can best take advantage of technology, in order to improve visitor experience. Let’s take a look at what we found.

A Post-pandemic Portrait

In order to explore this topic in detail, we took a look at a few of the pain points visitor attractions such as museums, art galleries and stately homes have seen since the beginning of 2019.

Facility closures hit all businesses where physical attendance is a core component. From hospitality to historical landmarks, there was a sense that the purpose of these very places had been removed, owing to the lack of visitors there to experience them. Art Fund, the UK’s national charity for art released an insightful report on the effects of COVID 19 on museums and art galleries, citing “a third of museum directors still remain concerned about their long-term survival, despite 88% of respondents having received emergency or recovery support alongside the generosity of the public and philanthropic bodies.”. They also reported earlier this year that visitor numbers were down an average of 39%, with museums and galleries relying primarily on digital interventions to gain visitor interest.

In addition to financial challenges post-pandemic, movements for the returning of artefacts to their region of origin are gaining momentum. Criticism from activist groups globally, and a general reassessment of curation at many major institutions has seen a rise in the repatriation of artefacts, giving rise to growing public support for the disassembling of the post-colonial appeal of holding onto pieces well beyond custodianship.

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Innovation of the Institution

Museums and galleries are places of storytelling. From the past through to the future, cultural institutions sit at the heart of public education, and perhaps most importantly in the age of disinformation, as keystones of truth; vital lifelines for the upkeep of balanced, evidence based knowledge.

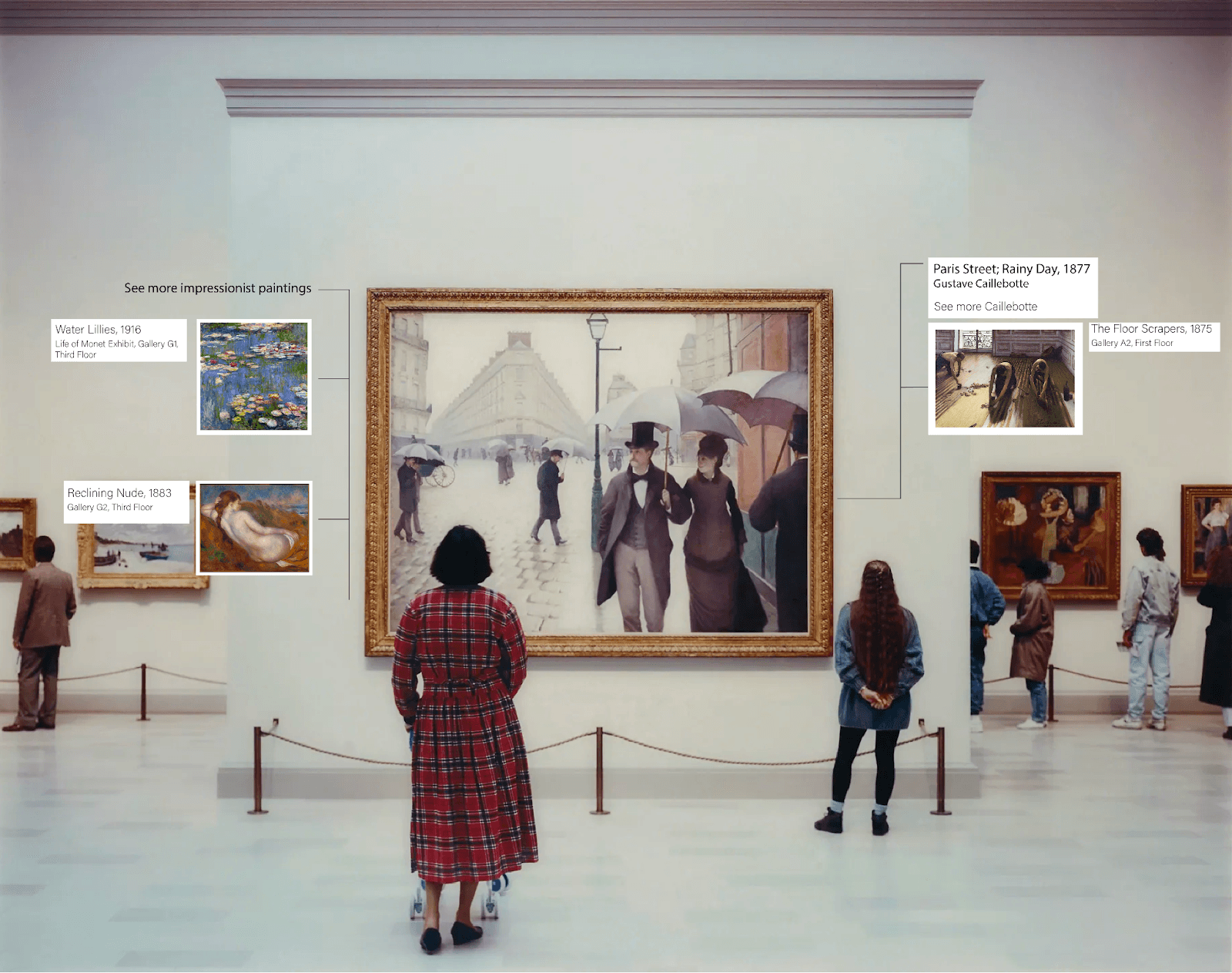

The key for innovation within these spaces, as we see it, is an online format that complements the physical world, while allowing for multistate discovery. But what do we mean by this? And how can we achieve it?

The Multistate Museum

In the last decade, cultural institutions have been on a light-speed journey, jumping from one technological innovation to another in order to keep up with trends and increase visitor engagement. Audio guides apps came first, then VR, then once mobiles caught up, AR. Each time a new technology was introduced, a disconnect occurred between the two primary parties within the venues, the patrons and the artefacts. We put pixels before people. And it’s time to put that right.

In our vision for the multistate museum, we propose focus on 3 key areas:

- Unintrusive guidance and information infrastructure.

- Extended experiences off site.

- The democratisation of access to artefacts and information.

Unintrusive guides: Putting humans back in the picture

There is a time and a place for looking down at your phone, being guided round an impressive exhibition space isn’t one. Audio guides are a fantastic intervention to help users navigate around a space, but there are a few things that can be done to improve the experience beyond keying in numbers from a sign in front of an exhibit.

SFMOMA employs a fantastic solution to this problem. Their audio guide app utilises wifi connection points to triangulate a users location within the galleries, allowing for a seamless viewing experience where the occupant keeps their hands off their phone. This allows them instead to immerse themselves fully in the works of art around them.

Additionally, audio guides have a tendency to feel unnervingly spectral, and function more like an audiobook than a real life guide. The most successful audio guides we have experienced are those which seek to form a bond with their participant. Imagine this scenario:

You’ve just hit play on your audio guide at the museum, and are about to walk through the doors to a grand hall. Which of these impresses you the most?

- “You’re now entering the grand hall of the Arch Museum of Modern Art (AMOMA for short). The museum is split up into three halls: Sculpture, paintings and artefacts. You can access all of these from the main hall.”

- “You’re now entering the grand hall of the AMOMA. Direct your eyes to the grand staircase in front of you, now allow your gaze to ascend it… keep going… See that? Notice the detailing of the hammerbeam roof? (give a moment for appreciation) It dates back to 1422. From under its arches you can find access to the 3 exhibition halls, Sculpture, paintings and artefacts, which would you like to explore first?”

The second is slightly longer, but in a world of increased immersion, the importance of extending this to something as consistent as an audio guide cannot be underestimated. The public is told what to do by digital voices in all kinds of daily interactions. However, in a space as special as a museum or an art gallery, they want these voices to have personality, respond to their desires and put them in control - that’s the future of audio.

Excitement Before, During and After the Visit

How do we allow access to artefacts within the museum to a wider audience than just those within travelling distance, and in doing so replicate the sense of wonder and engagement that comes with having attended an exhibition in person? By opening up cultural venues to an expanded visitor experience that extends beyond the boundaries of the site, we can increase learning opportunities and visitor retention rate simultaneously. There are many great examples of how this works in practice, from the Smithsonian to the British Natural History Museum, where websites and apps combine to increase the excitement in anticipation of the visit, and provide patrons with a little something extra to talk about when the leave the venue

A user flow of how this looks works a little bit like this:

- Users buy tickets on their chosen ticketing website, or that of the venue.

- A user is instructed to download the venue’s app and is greeted by a homescreen.

- The user inputs their visit date and is able to view:

- Exhibits taking place at that time

- Accompanying information around their ticket

- Details of occupancy at the venue for a series of visiting times (allowing for them to make informed decisions based on their accessibility requirements).

- The user reviews the information and is able to select certain exhibits to view at times of optimum occupancy for their schedule and requirements

- The user attends the gallery, using the app as their guide.

- The user leaves the venue, with a detailed overview of what they saw, and extra resources for learning and exploration.

- The user is encouraged to keep the app downloaded to review these assets, allowing for push notifications to be used to encourage future attendance at relevant events and exhibitions.

- The user can also donate via the app following the experience and reviewing of the extra information they have received.

The use of an app in this situation limits issues of connectivity on sites with catacombs or basement floors which may not actively accommodate wifi or reception signals.

Information Democratisation

We mentioned before the concept of museums being custodians of the past, but they can also be muses for the future. In democratising artefacts, we open a world of new possibilities for people curious about them. But how does technology help us in this cause, and what impact does it have? Most commonly, democratisation of information means placing it in the hands of those who need it, as easily and as beneficial as possible. Again, the Smithsonian takes this to the next level.

Their collection contains 155 million artefacts and objects, but less than 1% can be on display at their museums at any one time. Not only would presenting all of them be a logistical nightmare, it would actually increase barriers to access. Galleries hundreds of metres long would need to be erected, with endless corridors and floors, limiting their availability to those with accessibility requirements.

Through digitisation of these artefacts, the museum is able to provide a centralised, democratised repository for their collection, allowing access by anyone at any time to these objects. They do this by 3D scanning them, and uploading them to an online catalogue. Users can go, view a stegosaurus, and then explore the asset in 3D right in front of them using AR via their mobile phone. Now we’re not speculating how many people use these assets to compare them in size to their dog or cat, maybe even their toddler, but the point is that the information is there, in accessible form, for anyone to explore as they like.

In digitising the assets, we also deal with a barrier to the repatriation of artefacts. If they’re scanned and displayable in digital form, they can be seen by anyone, anywhere, removing the need for physical artefacts to remain in museums and galleries remote from their origin.

Additionally, we deal with the practicalities of space. There is only so much room in a gallery or exhibition hall so by setting these artefacts digitally, we’re able to allow the public access to them alongside related physical objects, telling a richer, expanded story about them.

What are we getting at?

In summary, the future of museums isn’t strictly digital, nor is it a return to purely physical. In the 21st century, information access is essential, and in combining these two into an multistate experience, we can remove boundaries to access to information. This in turn increases the value that visitors place on artefacts and their stories through curated experiences, and promotes the importance of cultural institutions within society.